Assessment of nutritional status from birth upto 18 years of age

By

Dr. Pallab Kanti Nath

MBBS, MD

Assessment of nutritional status from birth to 18 years of age

Introduction

The science of Human Nutrition can be defined as “the science of diet and its interactions with growth, development, physiology, metabolism, and composition of the human body . It involves the role of nutrition in normal and abnormal individuals, the impact of nutrition on health and disease, and the interactions between diet, host, and environment .” (1)

Nutrition plays a major role in health, prevention of disease, and recovery from illness. Therefore, we should have an understanding and awareness about nutrition in order to optimally promote health maintenance, prevent diseases, facilitate recovery from illness, and augment the treatment of medical and surgical diseased states. Awareness and application of nutrition in medical practice has a major impact on the health care in our society.

Malnutrition problems, like other health problems, can affect individuals, families and often communities as a whole. This is not surprising, considering that the roots of malnutrition related problems lie in socioeconomic status and cultural practices that are usually shared by many individuals in a given community. Thus communities afflicted by poverty and adverse living conditions may have a great majority of children and mothers showing signs of undernutrition, whereas affluent communities may have substantial number of individuals with diet-related problems like that of being overweight and obese.

Through centuries food has been recognized as important for human beings, in health and disease. The history of man to a large extent has been a struggle to obtain food. Until the turn of the nineteenth century the science of nutrition had a limited range. Protein, carbohydrate and fat had been recognized early in the 19th century as energy-yielding foods and much attention was paid to their metabolism and contribution to energy requirements (2).

The discovery of vitamins “rediscovered” the science of nutrition. Between the two World Wars, research on protein gained momentum. By about 1950, all the presently known vitamins and essential amino acids had been discovered (2).

Nutrition gained recognition as a scientific discipline, with roots in physiology and biochemistry. In fact, nutrition was regarded as a branch of physiology and taught as such to medical students (2).

Many advances were made during the past 50 years regarding the knowledge of nutrition and in the practical application of that knowledge. Specific nutritional diseases were identified and technologies developed to control them.( eg. Protein Energy Malnutrition, Endemic Goitre, Nutritional Anaemia, Nutritional Blindness and Diarrhoeal Diseases (2).

While attention was concentrated on nutrition deficiency diseases during the first decades of the 20th century, the science of nutrition was extending its influence into other fields as well like agriculture, animal husbandry, economics and sociology. This led to "green revolution" and "white revolution" in India and increased food production (2). However, studies on diet and state of nutrition of people in India showed that poorer sections of the population continued to suffer from malnutrition despite increased food production. The result was that, for the first time the problem of nutrition began to attract international attention as a cause of social problems (3).

But, to have a qualitative as well as quantitative understanding of the magnitude of health problems related to nutrition, a method for assessment of the nutritional status in the human population was required. A major development in this regard took place in 1932 in Berlin when The health Organization of the League of Nations (HOLN) held its first conference to discuss the physical, clinical, and physiological aspects of nutrition assessment. This conference motivated the publication of procedures needed for conducting nutrition surveys (4). Subsequently, the monograph published by the Technical Commission of Nutrition of the Health Organization (TCNHO) became the first organized work on dietary standards (4). Around the same period, Bigwood's Guiding Principles for Studies on the Nutrition of Populations provided detailed procedures for conducting nutrition surveys which became a classic reference for conducting nutrition surveys (5). Although the initial methods have been revised but, the basic principles behind nutritional assessment have remained same over the past years (6).

In the 1940s under the auspices of the United Nations the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the World Health Organization (WHO) were established. Representatives from each of the organizations were selected to form a Joint Expert Committee on Nutrition. In 1949, these representatives compiled information on nutritional status, dietary patterns, food supplies and the economics of particular populations and recommended the establishment of nutrition policies for each nation. In 1951, the Joint Commission of the WHO published a report that emphasized on anthropometric, clinical, and dietary data, but it did not make recommendations or set standards (5) (6).

Significant advances have since been made. The association of nutrition with infection, immunity, fertility, maternal and child health and family health have engaged scientific attention. More recently, a great deal of interest has been focused on the role of dietary factors in the pathogenesis of non-communicable diseases like coronary heart disease, diabetes and cancer etc.

One of the significant developments during the recent years is that the science of nutrition has linked itself to epidemiology. This association has given birth to newer concepts in nutrition such as epidemiological assessment of nutritional status of communities, nutritional and dietary surveys, nutritional surveillance, nutritional and growth monitoring, nutritional rehabilitation, nutritional indicators and nutritional interventions — all parts of what is broadly known as nutritional epidemiology (2).

Assessment of Nutritional Status

To understand and correlate between the various factors that affect the nutritional status of a population and its implications on the development of the society as a whole, the foremost important step is assessment of the nutritional status of the population. The assessment of nutrition therefore is one of the 1st steps in formulation of any public health strategy to combat malnutrition.

The various Methods of Nutritional Assessment from birth upto 18 years of age

The nutritional status of an individual is often the result of many interrelated factors. It is influenced by the adequacy of food intake both in terms of quantity and quality and also by the physical health of the individual (2). The assessment of nutritional status therefore involves various techniques with a multi-angled approach aimed at covering all the different stages in the natural history of nutritional diseases including the prepathogenesis phase as shown in the figure below.

The sequence of nutritional deficiency and specificity of assessment of the nutritional status can be also described using the following flow chart (7):-

Nutritional Status can be therefore, assessed by the following methods:-

Direct methods

|

Indirect methods

|

Clinical examination

|

Assessment of dietary Intake

|

Anthropometry

|

Vital Statistics

|

Biochemical evaluation

|

Ecological studies

|

Functional Assessment

|

|

Biophysical & Radiological examination

|

|

Methods of Nutritional Assessment (2,7)

The various methods used for appraisal of nutritional status are not mutually exclusive; on the contrary, they are complementary to each other as discussed below:-

DIRECT METHODS

1. Clinical methods

Clinical examination assesses the level of health of an individual in relation to the food they consume. When two or more clinical signs characteristic of a deficiency disease are present simultaneously, their diagnostic significance is greatly enhanced (7). It is also the simplest and the most practical method of ascertaining the nutritional status of a group of individuals(2). A WHO Expert Committee (8) classified signs used in nutritional surveys into three categories as those:

a. not related to nutrition, e.g., alopecia, pterygium

b. that need further investigation, e .g. , malar pigmentation, corneal vascularisation, geographic tongue

c. known to be of value, e.g., angular stomatitis, Bitot's spots, calf tenderness, absence of knee or ankle jerks (beri-beri), enlargement of the thyroid gland (endemic goitre), etc.

The following are some of the signs and symptoms which are found to be associated with nutritional inadequacy (9) in our study population:-

Site

|

Sign

|

Deficiency

|

General appearance

|

Loss of subcutaneous fat

|

Calories

|

Sunken or hollow cheeks

|

Calories, fluid

|

Hair

|

Easily plucked hair, alopecia

|

Protein

|

Dry, brittle hair

|

Protein,Biotin

|

Corkscrew hairs

|

Vit C

|

Nails

|

Spooning

|

Iron

|

Transverse depigmentation

|

Protein

|

Skin

|

Dry and scaly flaky paint

|

Vitamin A, zinc

|

Nasolabial seborrhea

|

Essential fatty acid, riboflavin

|

Psoriasiform rash

|

Vitamin A, zinc

|

Pallor

|

Iron, vitamin B12, folate

|

Follicular hyperkeratosis

|

Vitamin A, essential fatty acid

|

Perifollicular hemorrhage

|

Vitamin C

|

Easy bruising

|

Vitamin K or C

|

Hyperpigmentation

|

Niacin

|

Eyes

|

Night blindness

|

Vitamin A, zinc

|

Photophobia, xerosis

|

Vitamin A

|

Conjunctival inflammation

|

Riboflavin, vitamin A

|

Retinal field defect

|

Vitamin E

|

Mouth

|

Glossitis

|

Riboflavin, pyridoxine, niacin, folic acid, vitamin B12, iron

|

Bleeding gums

|

Vitamin C, riboflavin

|

Angular stomatitis

|

Riboflavin, pyridoxine, niacin

|

Cheilosis

|

Riboflavin, pyridoxine, niacin

|

Decreased taste or smell

|

Zinc

|

Tongue fissuring

|

Niacin

|

Tongue atrophy

|

Riboflavin, niacin, iron

|

Loss of tooth enamel

|

Calcium

|

Neck

|

Goitre

|

Iodine

|

Parotid enlargement

|

Protein

|

Heart

|

High output failure

|

Thiamin

|

Chest

|

Respiratory muscle weakness

|

Protein, phosphorus

|

Abdomen

|

Ascites

|

Protein

|

Hepatomegaly

|

Protein, fat

|

Extremities

|

Edema

|

Protein

|

Bone tenderness

|

Vitamin D

|

Bone/joint pain

|

Vitamin A or C

|

Muscle pain

|

Thiamin

|

Joint swelling

|

Vitamin C

|

Muscle

|

Atrophic muscles, Decreased grip strength

|

Protein

|

Neurological

|

Dementia

|

Thiamin, vitamin B12, folate, niacin

|

Acute disorientation

|

Phosphorus, niacin

|

Nystagmus

|

Thiamin

|

Ophthalmoplegia

|

Thiamin

|

Wide-based gait

|

Thiamin

|

Peripheral neuropathy

|

Thiamin, pyridoxine, vitamin E

|

Loss of vibratory sense

|

Vitamin B12

|

Loss of position sense

|

Vitamin B12

|

Tetany

|

Calcium, magnesium

|

Paresthesias

|

Thiamin, vitamin B12

|

Wrist or foot drop

|

Thiamin

|

Diminished reflexes

|

Iodine

|

Clinical examination for assessment of nutritional status has got many advantages as well as certain disadvantages also.

Advantages include the following (7):-

· For clinical examination cooperation of the subject can be achieved easily because the procedure is noninvasive and the symptoms are observed externally.

· This method is reliable and easy to organise.

· Exact Age of the subject need not be ascertained always.

· Symptoms are specific to a particular nutrient.

· This method is not very expensive. It does not require elaborate apparatus and reagents.

However, clinical signs also have some disadvantages as well (2):-

· Malnutrition cannot be quantified on the basis of clinical signs only.

· Many deficiencies are unaccompanied by physical signs.

· There is lack of specificity and most of the physical signs are subjective in nature.

To minimize subjective and errors in clinical examination, standard survey forms or schedules have been devised covering all areas of the body (2).

2. Anthropometry

Anthropometric measurements can reflect changes in morphological variation due to inappropriate food intake or malnutrition. A variety of anthropometric measurements can be made either involving the whole body or parts of the body. In anthropometric measurements, there is no single permanent standard as because uniform growth pattern is not seen to occur equally all over the world and also in subsequent generations. Therefore, Local standards have to be developed for various ethnic groups and populations (7). The assessment of growth may be longitudinal or cross-sectional. Longitudinal assessment of growth entails measuring the same child at regular intervals. This provides valuable data about a child's progress. Cross-sectional studies are also essential to compare a child's growth with that of his peers. Cross-sectional comparisons involve large number of children of the same age. These children are measured and the range of their measurements (e.g., weight, height) is plotted, usually on percentile charts (2).

Components of Anthropometric Assessment:

a) Weight-for-age

Body weight is the most widely used and simplest anthropometric measurement for evaluation of nutritional status. It indicates the body mass and is a composite of all body constituents like water, mineral, fat, protein and bone. It reflects more recent nutritional status than does height. Serial measurements of weight, as in growth monitoring are more sensitive indicators of changes in nutritional status than a single measurement at a point of time. In clinical practice however, the use of whole body indices may sometimes be limited as in cases when a child has ascites, fluid retention, or a large solid tumor which can confound the weight-based indices.

For measuring body weight, beam or lever actuated scales, with an accuracy of 50-100g can be used. Beam balances have been used in ICDS programme. Periodically scales have to be calibrated for accuracy using known weights. The zero error of the weighing scale should be checked before taking the weight and corrected as and when required (7). According to WHO(10), children should be weighed using a scale with the following features:

· Solidly built and durable

· Electronic (digital reading)

· Measures up to 150 kg

· Measures to a precision of 0.1 kg (100g)

· Allows tared weighing

“Tared weighing” means that the scale can be re-set to zero (“tared”) with the person just weighed still on it. Thus, a mother can stand on the scale, be weighed, and the scale tared. While remaining on the scale, if she is given her child to hold, the child’s weight alone appears on the scale. Tared weighing has two advantages (10):

· There is no need to subtract weights to determine the child’s weight alone (reducing the risk of error).

· The child is likely to remain calm when held in the mother’s arms for weighing.

There are many types of scales currently in use like:-

Bathroom scales may give errors upto 1.5kg (7). Bathroom scales are therefore not recommended. WHO recommends the use of UNISCALE (made by UNICEF) (10). It has the recommended features of a weight scale as mentioned before. It is powered by a lithium battery that is good for a million measurement sessions. The scale has a solar on-switch, so it requires adequate lighting to function. Footprints may be marked on the scale to show where a person should stand.

Procedure for measuring weight

1. If the child is less than 2 years old or is unable to stand, tared weighing should be done:

The scale is placed on a flat, hard, even surface.

Since the scale is solar powered, there must be enough light to operate the scale. To turn on the scale, the solar panel has to be covered for a second. When the number 0.0 appears, the scale is ready for use.The mother has to remove her shoes and step on the scale to be weighed alone first. After the mother’s weight appears on the display, she is made to remain standing on the scale. The reading is reset to zero by covering the solar panel of the scale (thus blocking out the light). Then the child is given to the mother to hold. The child’s weight now appears on the scale which can be recorded (10).

2. If the child is 2 years or older:

If the child stands still, then he/she can be measured alone. The child should be Undressed in order to obtain an accurate weight. A wet diaper, or shoes and jeans, can weigh more than 0.5 kg. Babies should be weighed naked. They should be wrapped in a blanket to keep them warm until weighing. Older children should remove all but minimal clothing, such as their underclothes.

If it is too cold to undress a child, or if the child resists being undressed and becomes agitated, then clothed child should be weighed, but a note in the Growth Record that the child was clothed has to be kept.If it is socially unacceptable to undress the child, removal of as much of the clothing as possible should be tried (10).

Birth-weight measurement:

The birth—weight should be taken preferably within the first hour of life, before significant post—natal weight loss has occurred. The naked baby should be placed on a clean towel on the scale pan (2).

In home delivery, weight can be taken by placing the baby in a sling bag using a Salter weighing scale. The child is weighed to the nearest 100 g (2).

Nutritional status assessment from weight

Measurement of weight and rate of gain in weight are the best single parameters for assessing physical growth. A single weight record only indicates the child's size at the moment, it does not give any information about whether a child’s weight is increasing, stationary or declining. This is because, normal variation in weight at a given age is wide. Ideally what is important is careful measurements at repeated intervals:-

· Every month, from birth to 1 year

· Every 2 months during the second year

· Every 3 months thereafter upto 5 years of age.

This has been recommended because this age group is at the geatest risk from growth faltering. By comparing the measurements with reference standards of weight of children of the same age, the trend of growth becomes obvious. This is best done on growth chart. Serial weighing is also useful to interpret the progress of growth when the age of the child is not known. Thus, without the aid of a growth chart, it is virtually impossible to detect changes in the rate of growth, such as sudden loss of weight or halt in gain. Each baby should have its own growth chart (2).

In different parts of India, the average birth weight of a child ranges between 2.7 and 2.9 kg. The term ‘Low birth weight’ has been defined as a birth weight of less than 2.5 kg (up to and including 2499 g), the measurement being taken preferably within the first hour of life, before significant postnatal weight loss has occurred. Low birth weight babies are further classified into 2 groups (2):-

I. Pre-term Babies: These are babies born before 37 weeks of gestation. Their intrauterine growth may be normal. That is, their weight, length and development may be within normal limits for the duration of gestation. Given good neonatal care, these babies can catch up growth and by 2 to 3 years of age will be of normal size and performance.

II. Small-For-Date (SFD) Babies : These may be born at term or pre-term. They weigh less than the 10th percentile for the gestational age. These babies are the result of retarded intrauterine foetal growth.

A baby should gain at least 500 gram wt. per month in the first three months of life. The children who gain less weight are malnourished. It is usual for babies to gain about 1 kg a month, especially in the first 3 months.

Healthy babies on an average double their birth wt. by 5 months; treble it by the end of first year and quadruple it by the age of two years (2).

During the first year, wt. increases by about 7 kg. After that, the increase in weight is not so fast -- only about 2.5 kg during the second year and from then until puberty wt increases by about 2 kg per year (2).

b) Height(Length)-for-age

The height of an individual is influenced both by genetic and environmental factors. The maximum growth potential of an individual is decided by hereditary factors, while among the environmental factors, the most important being nutrition and morbidity, determine the extent of exploitation of that genetic potential. Height is affected only by long-term nutritional deprivation, it is considered an index of chronic or long duration malnutrition (7).

Depending on a child’s age and ability to stand, the method of measurement is decided. A child’s length is measured lying down (recumbent) whereas, Height is measured standing upright. Decision as regards the selection of the method of measurement is decided by the following criteria (10):-

· If a child is less than 2 years old, recumbent length is measured.

· If the child is aged 2 years or older and able to stand, standing height is measured.

In general, standing height is about 0.7 cm less than recumbent length. This difference was taken into account in developing the WHO growth standards used to make the charts in the Growth Record. Therefore, it is important to adjust the measurements if length is taken instead of height, and vice versa (10):-

· If a child less than 2 years old does not lie down for measurement of length, then standing height can be measured but, 0.7 cm must be added to convert it to length.

· If a child aged 2 years or older cannot stand, then recumbent length can be measured but 0.7 cm should be subtracted to convert it to height.

Procedure for measuring height

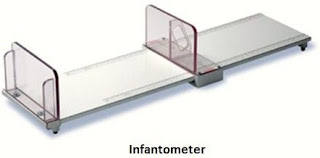

Equipment needed to measure length is a Length Board (also called an Infantometer). It should be placed on a flat, stable surface such as a table. To measure height, a

Height Board is used(also called a Stadiometer). It is mounted at a right angle between a level floor and against a straight, vertical surface such as a wall or pillar.

Before the measurement shoes, socks and hair ornaments (if any) should be removed. If braids interfere with the measurement of length/height, they should be undone. When measurement is to be done on a young child the mother is needed to help with measurement and to

soothe and comfort the child. She should be explained the reasons for the measurement and the steps in the procedure for ensuring proper help.

Measurement of length:

The 1st measurement of length should be done within 3 days of life (2). The length board is covered with a thin cloth or soft paper for hygiene and for the baby’s comfort. Explanation should be given to the mother that she will need to place the baby on the length board herself and then

help to hold the baby's head in place while the measurement is being taken. She should be showed where to stand when placing the baby down (i.e. opposite to the person doing the measurement) on the side of the length board away from the tape. Also placement of the baby’s head should be showed to her (against the fixed headboard) so that she can move quickly and surely without distressing the baby.

When the mother understands the instructions and is ready to assist:

· She is asked to lay the child on its back with its head against the fixed headboard, compressing the hair.

· Quickly the head should be positioned so that an imaginary vertical line from the ear canal to the lower border of the eye socket is perpendicular to the board. (The child’s eyes should be looking straight up.) The mother is asked to move behind the headboard and hold the head in this position. Standing on the side of the length board from where the measuring tape can be seen footboard is moved:-

· It must be checked that the child lies straight along the board and does not change position. Shoulders should touch the board, and the spine should not be arched. The mother should be asked to inform if the child arches the back or moves out of position.

· Now the child’s legs are held down with one hand and the footboard is moved with the other. Gentle pressure is applied to the knees to straighten the legs as far as they can go without causing injury. (Note: it is not possible to straighten the knees of newborns to the same degree as older children. Their knees are fragile and could be injured easily, minimum pressure should be applied.)

If a child is extremely agitated and both legs cannot be held in position, measurement with one leg in position is done.

· While holding the knees, the footboard is pulled against the child’s feet. The soles of the feet

should be flat against the footboard, toes pointing upwards. If the child bends the toes and

prevents the footboard from touching the soles, the soles can be scratched slightly and when the child straightens the toes the footboard is to be slid in quickly.

· The measurement is Read and recorded in centimetres to the last completed 0.1 cm.

Check that shoes, socks and hair ornaments have been removed.

In case of a small child working with the mother, kneel down in order to get down to the level of the child:

· Help the child to stand on the baseboard with feet slightly apart. The back of the head, shoulder blades, buttocks, calves, and heels should all touch the vertical board. This alignment may be impossible for an obese child, in which case, help the child to stand on the board with one or more contact points touching the board. The trunk should be balanced over the waist, i.e., not leaning back or forward.

· Ask the mother to hold the child’s knees and ankles to help keep the legs straight and feet flat, with heels and calves touching the vertical board. Ask her to focus the child’s attention, soothe the child as needed, and inform you if the child moves out of position.

· Position the child’s head so that a horizontal line from the ear canal to the lower border of the eye socket runs parallel to the baseboard. To keep the head in this position, hold the bridge between your thumb and forefinger over the child’s chin.

· If necessary, push gently on the tummy to help the child stand to full height.

· Still keeping the head in position, the other hand is to be used to pull down the headboard to rest firmly on top of the head and compress the hair.

· Read the measurement and record the child’s height in centimetres to the last completed 0.1 cm.

The length of a baby at birth is about 50 cm. It increases by about 25 cm during the first year and by another 12 cm during the second year. During growth spurt, boys add something like 20 cm in their height, and girls gain about 16 cm. The spurt is followed by a rapid slowing of growth. Indian girls reach 98 per cent of their final height on an average by the age of 16.5 years, and boys reach the same stage by the age of 17.75 years (2).

Height is a stable measurement of growth and nutritional status, as opposed to body weight. Whereas weight reflects only the present health status of the child, height indicates the events in the past also (2).

c) Weight-for-height

Weight-for-height is now considered more important than weight alone. It helps to determine whether a child is within range of "normal" weight for his height (2).

For example, a child on the 75th centile of both his height and weight is neither over—weight nor under—weight, but a child on the 75th centile of his weight chart and the 25th centile of his height chart is clearly overweight.

d) Mid-arm Circumference

Arm circumference yields a relatively reliable estimation of the body's muscle mass, the reduction of which is one of the most striking mechanisms by which the body adjusts to inadequate energy intakes (2).

Arm circumference cannot be used before the age of one year; between ages one and five years, it hardly varies (2).

An arm circumference exceeding 13.5 cm is a sign of a satisfactory nutritional status, between 12.5 and 13.5 cm it indicates mild—moderate malnutrition and below 12.5 cm, severe malnutrition (2).

Procedure to locate mid-point of upper arm:

On the left hand, the mid-point between the tip of the acromion of scapula and tip of the olecranon of the fore-arm bone, ulna is located with the arm flexed at the elbow and marked with a marker pen (7).

Classifications for assessment of Nutritional Status using the aforementioned parameters:

1) Gomez' classification (2):

Gomez' classification is based on weight retardation. It locates the child on the basis of his or her weight in comparison with a normal child of the same age. In this system, the "normal" reference child is in the 50th centile of the Boston standards. The cut—off values were set during a study of risk of death based on weight for age at admission to a hospital unit. This classification therefore, has a prognostic value for hospitalized children with PEM.

Grade

|

Weight-for-age

|

Normal nutritional status

|

Between 90 & 110%

|

1st*,mild malnutrition

|

Between 75 and 89%

|

2nd*,moderate malnutrition

|

Between 60 and 74%

|

3rd*,severe malnutrition

|

Under 60%

|

The disadvantages are :

· A cut-off-point of 90 per cent of reference is high and thus some normal children may be classified as 1st degree malnourished.

· By measuring only weight for age it is difficult to know if the low weight is due to a sudden acute episode of malnutrition or to long-standing chronic undernutrition (2).

2) Waterlow's classification (2):

When a child's age is known, measurement of weight enables almost instant monitoring of growth & measurement of height shows the effect of nutritional status on long-term growth.

Waterlow's classification defines two groups for protein energy malnutrition:

· malnutrition with retarded growth, in which a drop in the height/age ratio points to a chronic condition— shortness, or stunting.

· malnutrition with a low weight for a normal height, in which the weight for height ratio is indicative of an acute condition of rapid weight loss, or wasting.

This combination of indicators makes it possible to label and classify individuals with reference to two poles:

· Children with insufficient but well-proportioned growth.

· Those with a normal height, but who are wasted.

Nutritional status

|

Stunting

(% of height/age)

|

Wasting

(% of weight/height)

|

Normal

|

>95

|

>90

|

Mildly impaired

|

87.5 - 95

|

80 – 90

|

Moderately impaired

|

80 - 87.5

|

70 – 80

|

Severely impaired

|

<80

|

<70

|

3) Indian Academy of Pediatrics (IAP) Classification(based on weight-for-age) (11):

IAP designates a weight of more than 80 percent of expected for age as normal. Grades of malnutrition are :

· Grade I (71-80%)

· Grade II (61-70%)

· Grade III (51-60%)

· Grade IV (£50%)

of expected weight(50th percentile of reference standard) for that age.

Alphabet K is postfixed in presence of edema.

IAP classification is simple and the cut offs are suitable for Indian population. However, the disadvantage is that it does not take in account the child's height. The weight is also dependent on height besides the built; thus children who are short statured (not necessarily because of nutritional deprivation) are also misclassified as PEM by this classification (11).

4) Welcome trust Classification (11):

This is also based on deficit in body weight for age and presence or absence of edema.

· Children weighing between 60-80 per cent of their expected weight for age with edema are classified as kwashiorkor.

· Those weighing between 60-80 per cent of expected without edema are known as having undernutrition.

· Those without edema and weighing less than 60 per cent of their expected weight for age are considered to be having marasmus.

· Marasmic kwashiorkor is applied to children with edema and body weight less than 60 percent of expected.

5) Age Independent Anthropometric Indeces (11):

THE GROWTH CHARTS

The growth chart or "road-to-health" chart was first designed by David Morley and was later modified by WHO. It is a visible display of the child's physical growth and development. It is designed primarily for the longitudinal follow-up (i.e. growth monitoring) of a child, so that changes over time can be interpreted (2).

WHO has developed growth standards based on a sample of children from six countries: Brazil, Ghana, India, Norway, Oman, and the United States of America. The data was obtained from WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study (MGRS). The study followed term babies from birth to 2 years of age, with frequent observations in the first weeks of life. Another group of children, age 18 to 71 months, were measured once, and data from the two samples were combined to create the growth standards for birth to 5 years of age (12).

By including children from many countries who were receiving recommended feeding and care, the MGRS resulted in prescriptive standards for normal growth, as opposed to simply descriptive references. The new standards show what growth can be achieved with recommended feeding and health care (e.g. immunizations, care during illness). The standards can be used anywhere in the world, since the study also showed that children everywhere grow in similar patterns when their nutrition, health, and care needs are met (12).

The nutritional status can be therefore easily assessed for any child using these standardized charts. For the assessment WHO has provided charts for both boys and girls based on:

o length/height-for-age

o weight-for-age

o weight-for-length/height

o BMI (body mass index)-for-age

Each of the graphs have got the following features (10):

o x-axis – the horizontal reference line at the bottom of the graph. In the Growth Record graphs, some x-axes show age and some show length/height. Plot points on vertical lines corresponding to completed age (in weeks, months, or years and months), or to length or height rounded to the nearest whole centimetre.

o y-axis – the vertical reference line at the far left of the graph. In the Growth Record graphs, the y-axes show length/height, weight, or BMI. Plot points on or between horizontal lines corresponding to length/height, weight or BMI as precisely as possible.

o Plotted point – the point on a graph where a line extended from a measurement on the x-axis (e.g. age) intersects with a line extended from a measurement on the y-axis (e.g. weight)

Further details explained with an example as follows (13):-

Shown above is a Growth Chart for boys showing Weight-for-length from Birth to 2 years of age. The line labeled 0 on the chart represents the median value or the average value. The other curved lines are z-score lines, which indicate distance from the average. [ Z-scores may also be called standard deviation (SD) scores.]

Z-score lines on the growth charts are numbered positively (1, 2, 3) or negatively (-1, -2,-3). In general, a plotted point that is far from the median in either direction may represent a growth problem, although other factors must be considered, such as the growth trend, the health condition of the child and the height of the parents.

The points on the Growth chart are read as follows (13):

o A point between the z-score lines -2 and -3 is “below -2.”

o A point between the z-score lines 2 and 3 is “above 2.”

o If point is exactly on the z-score line, it is considered in the less severe category.

Interpretation of the charts is easy and is done based on the following table provided by WHO (13):

Trends on growth charts

“Normally” growing children follow trends that are, in general, parallel to the median and z-score lines. Most children will grow in a “track,” that is, on or between z-score lines and roughly parallel to the median; the track may be below or above the median. Children who are growing and developing normally will generally be on or between -2 and 2 z-scores of a given indicator (13).

When interpreting growth charts, one should be alert for the following situations, which may indicate a problem or suggest risk (13):

o There is a sharp incline or decline in the child’s growth line.

o The child’s growth line remains flat (stagnant); i.e. there is no gain in weight or length/height.

(note- Whether or not the above situations actually represent a problem or risk depends on where the change in the growth trend began and where it is headed. For example, if a child has been ill and lost weight, a rapid gain (shown by a sharp incline on the graph) can be good and indicate “catch-up growth.” Similarly, for an overweight child a slightly declining or flat weight growth trend towards the median may indicate desirable “catch-down.” It is very important to consider the child’s whole situation when interpreting trends on growth charts.)

Growth chart used in India

India has adopted the new WHO Child Growth Standards (2006) in February 2009, for monitoring the young child growth and development within the National Rural Health Mission and the ICDS. These standards are available for both boys and girls below 5 years of age (2).

A joint "Mother and Child Protection Card" has been developed which provides space for recording (2):

ü family identification and registration

ü birth record

ü pregnancy record

ü institutional identification

ü care during pregnancy

ü preparation for delivery

ü registration under Janani Suraksha Yojana

ü details about immunization procedures

ü breast-feeding and introduction of supplementary food

ü milestones of the baby

ü birth spacing and reasons for special care.

The chart is easily understood by the health workers and the mother, with a visual record of the health and nutritional status of the child. It it kept by the mother and brought to the health centre at each visit (2).

The growth chart shows:

ü normal zone of weight for age

ü undernutrition (below — 2 SD)

ü severely underweight zone (below — 3 SD).

It is the direction of growth that is more important than the position of dots on the line. The importance of the direction of growth is illustrated at the left hand, upper corner of the chart. Flattening or falling of the child's weight curve signals growth failure, which is the earliest sign of the protein- energy malnutrition and may precede clinical signs by weeks and months (2).

BMI measurement in Pediatric Population

WHO has published BMI charts as a part of growth chart in upto 5 years of age for both boys and girls. Interpretation is similar to the interpretation of WHO growth charts as mentioned above.

Center for Disease Control and Prevention has published BMI charts to measure BMI from 2-20 years of age group (14).

This chart shows the Body Mass Index (BMI) percentiles for boys from 2 to 20 years old. The curved lines show BMI percentiles. For example, the top curved line shows the 95% percentile, which means that 95% of children are at or under that value.The bottom of the chart shows ages, from 2 to 20 years. The left and right sides of the chart show BMI values.The chart shows that at age 2 years 95% of boys have a BMI less than 19.4 and 5% have one less than 14.6. At 20 years 95% of boys have a BMI less than 30.6, and 5% have one less than 19 (14).

The formula for calculation of BMI is same as that of adults:-

BMI = Weight in Kilograms

(height in meter)(height in meter)

However, it is interpreted differently from adults.

The CDC weight status classifications for use with the above table are as follows (14):

Percentile

|

Weight Status

|

>95th

|

Overweight

|

85th-95th

|

At Risk of Overweight

|

5th-85th

|

Normal

|

5th or less

|

Underweight

|

e) Head and chest circumference

At birth Head Circumference is about 34cm. It is about 2cm more than Chest Circumference. By 6-9 months, the two measurements become equal, after which the chest circumference overtakes the head circumference (2).

In severely malnourished children, this overtaking may be delayed by 3-4 years due to poor development of the thoracic cage (2).

For measurement Flexible fibre glass tape is used. The chest circumference is taken at the nipple level preferably in mid inspiration. The head circumference is measured by passing the tape round the head over the supra-orbital ridges of the frontal bone in front and the most protruding point of the occiput on the back of the head (7).

f) Skinfold thickness (at Triceps,Biceps,Subscapular and Suprailiac region)

A large proportion of total body fat is located just under the skin. Since it is most accessible, the method used is the measurement of skinfold thickness. It is a rapid and "non-invasive" method for assessing body fat. Several varieties of callipers (e.g., Harpenden skin callipers) are available for the purpose. The measurement is taken at all the four sites:

I. Mid-Triceps

II. Biceps,

III. Subscapular Region

IV. Suprailiac Region.

The sum of the measurements should be less than 40 mm in boys and 50 mm in girls. Unfortunately standards for subcutaneous fat do not exist for comparison. Further, in extreme obesity, measurements may be impossible. The main drawback of skinfold measurements for nutritional status assessment is their poor repeatability (2).

3. Biochemical evaluation

a. LABORATORY TESTS:

I. Haemoglobin estimation : It is the most important laboratory test that is carried out in nutrition surveys. Haemoglobin level is a useful index of the overall state of nutrition irrespective of its significance in anaemia. An RBC count and a haematocrit determination are also valuable (11,2,7).

II. Stool and urine : Stool should be examined for intestinal parasites. History of parasitic infestation, chronic dysentery and diarrhoea provides useful background information about the nutritional status of persons. Urine should also be examined for albumin and sugar (2) (7).

b. BIOCHEMICAL TESTS:

With increasing knowledge of the metabolic functions of vitamins and minerals, assessment of nutritional status by clinical signs has given way to more precise biochemical tests which may be applied to measure individual nutrient concentration in body fluids (e.g., serum retinol, serum iron) or detection of abnormal amounts of metabolites in urine (e.g., urinary iodine) frequently after a loading dose, or measurement of enzymes in which the vitamin is a known co-factor (for example in riboflavin deficiency) to help establish malnutrition in its preclinical stages. However, Biochemical tests are time-consuming and expensive. They cannot be applied on a large scale, as for example in the nutritional assessment of a whole community. They are often carried out on a subsample of the population. Most biochemical tests reveal only current nutritional status; they are useful to quantify mild deficiencies. If the clinical examination has raised a question, then the biochemical tests may be invoked to prove or disprove the question raised (2).

Some biochemical tests used in nutrition surveys (2):

Nutrient

|

Method

|

Normal value

|

Vitamin A

|

Serum retinol

|

20 mcg/dl

|

Thiamine

|

Thiamine pyrophosphate (TPP) stimulation of

RBC transketolase activity

|

1.00-1.23 (ratio)

|

Riboflavin

|

RBC glutathione reductase activity

stimulated by flavine

adenine dinucleotide

|

1.0-1.2 (ratio)

|

Folate

|

Serum folate

|

6.0mcg/ml

|

Red-cell folate

|

160mcgml

|

Vitamin B 12

|

Serum Vitamin B-12 concentration

|

160mg/L

|

Vitamin C

|

Leucocyte ascorbic acid

|

15 mcg/108 cells

|

Vitamin K

|

Prothrombin time

|

11-16 seconds

|

Protein

|

Serum albumin (g/L)

|

35

|

Transferrin (g/L)

|

20

|

Thyroid-binding pre-albumin (mg/L)

|

250

|

4. Functional Assessment

Functional indicators of nutritional status are diagnostic tests to determine the sufficiency of host nutritional status to permit cells, tissues, organs, anatomical systems or the host him/herself to perform optimally the intended nutrient dependent biological function (7).

Functional indices of nutritional status include cognitive ability, disease response, reproductive competence, physical activity, work performance and social and behavioural performance (7).

· Increased severity of malnutrition is associated with an increased heart rate response to the same submaximal work rate.

· Lactation performance is another functional index of individual nutriture. Milk volume is reduced in malnourished women as is fat and total energy content of the milk.

· Growth velocity also represents a functional index. Growth rates are suboptimal in PEM, zinc deficiency and iodine deficiency. The use of this index requires serial, accurate anthropometric measurements. Severe deficiencies of several nutrients will delay the onset of menarche.

· Social performance, the ability of an individual to interact with his or her peers and environment, is an index for functional nutritional status.

· Prenatally undernourished infants show several behavioural impairments that could negatively affect the development of social competence including reduced activity and less interaction with caretakers.

Functional indices have several potential advantages over static indices with respect to the validity of the information about nutritional status. A defective function may be uncovered despite an apparently "adequate" circulating or tissue level of a nutrient. Conversely, functional competence may be preserved even though the static index has fallen below the level of adequacy. Moreover, functional performance can to some extent be normalised on an individual basis rather than on a population standard, especially where performance can be assessed serially and a maximum output after nutritional supplement defined (7).

5. Biophysical and Radiological examination

These tests are used in specific studies where additional information regarding change in the bone or muscular performance is required. For example, Radiological methods are used in studying the change of bones in rickets, osteomalacia, osteoporosis and scurvy (7).

When clinical examination is suggestive, radiographic examinations are done as a part of nutritional assessment. Some examples of radiographic findings for nutritional assessment are (7):

· In rickets, there is healed concave line of increased density at distal ends of long bones usually the radius and ulna.

· In infantile scurvy there is ground glass appearance of long bones with loss of density.

· In beriberi there is increased cardiac size as visible through X-rays.

The main drawback of this method is that many sophisticated and expensive equipments along with technical knowledge are required in the interpreting data. It is also difficult to transport the equipments to interior parts of a village for organizing a nutritional assessment surveys (7).

Indirect methods

1. Assessment of dietary Intake (Diet Survey)

A diet survey provides information about dietary intake patterns of specific foods consumed and estimated nutrient intakes. It can help to indentify relative dietary inadequacies resulting in nutritional problems. Most of the time, the surveys are carried out for 7-10 days (7). Sometimes four season surveys are also done to increase the accuracy of the assessment.

Commonly utilized methods for Assessment of dietary Intake are:

· Inventory Method:

This method is often employed in institutions like hostels, army barracks, orphanages etc, where homogenous groups of people take their meals from a common kitchen. In this method, the amounts of food stuffs issued to kitchen as per the records maintained by the warden are taken into consideration. No direct measurement or weighing is done. A reference period of one week is desirable (7).

· Weighment Method:

I. WEIGHMENT OF RAW FOODS: The survey team visits the households, and weighs all food that is going to be cooked and eaten as well as that which is wasted or discarded. The duration of the survey may vary from 1 to 21 days, but commonly 7 days which is called "one dietary cycle" (2).

II. WEIGHMENT OF COOKED FOODS: Foods should preferably be analyzed in the state in which they are normally consumed, but this method is not easily acceptable among people (2).

· Expenditure Pattern Method (hostels, army barracks, orphanages etc.):

In this method, money spent on food as well as non-food items is assessed by administering a specially designed questionnaire. The reference period can be either a previous month or week.

This method, apparently is less cumbersome as it avoids actual weighing of foods. The reference period too is usually longer. In trained hands, both the methods, weighment and expenditure pattern method yield comparable results (7).

· Diet History:

This method is useful for obtaining qualitative details of diet and studying patterns of food consumption by the study group. The procedure includes assessment of the frequency or consumption of different foods daily or number of times in a week or fortnight or occasionally (7).

This method has been used to study meal pattern, dietary habits, food preferences and avoidances during physiopathological conditions like pregnancy, lactation, sickness etc. Infant weaning and breast feeding practices and the associated cultural constraints which are often prevalent in the community can also be studied by this method (7).

At times, information on approximate quantities of foods consumed like half a litre of milk per day required for a child in the family can also be collected (7).

· Oral Questionnaire (24 hour recall):

In this recall method of oral questionnaire diet survey, a set of standardised cups suited to local conditions are used. Information on the total cooked amount of each preparation is noted in terms of standardised cups. The intake of each food item by the specific individual in the family such as the preschool child, adolescent girl etc is assessed by using the cups. The cups are used mainly to aid the respondent recall the quantities prepared and fed to the individual members (2) (7).

· Chemical Analysis:

In this method, the individual is required to save a duplicate sample of each type of food eaten by him during the day. These samples are then collected and sent to the laboratory for chemical analysis.

It is the most accurate method but is costly and needs a good laboratory support (7).

· Dietary score:

This method is useful when one is trying to assess the dietary intake of specific nutrient e.g., iron content of diet. Depending on the content of iron, a food item is given a score. The frequency of intake of those foods is noted by questionnaire method. The frequency of consumption of foods, the total score and percentages are then calculated (7).

Even the best of diet surveys, give only an approximate estimate of foods and nutrients consumed by an individual under study. The methods do not give any idea about the amount food absorbed or utilized by his/her body.

The errors which occur generally in diet surveys are :

Ø memory lapses.

Ø long reporting period may give rise to a lot of errors.

Ø prestige and other considerations influencing the responses.

Ø non-response due to non-cooperation.

Ø conversion factors for the various crude local measures (inventory method).

Ø inaccurate weighing of food stuffs (weighment method).

Ø housewife deviating from the normal pattern of food consumption during the survey period (response errors).

Ø seasonal variations and improper selection of the reporting period.

Ø problems in the use of tables on nutritive value of foods.

Therefore, a combination of dietary, clinical and biochemical assessment is desirable for proper assessment of nutritional status of an individual or a community (7).

2. Vital Statistics

An analysis of vital statistics — mortality and morbidity data — will identify groups at high risk:

· Mortality in the age group 1 to 4 years is particularly related to malnutrition. In developing countries, it may be as much as 20 times than that in countries such as Australia, Denmark or France (2).

· The other rates commonly used for this purpose are :

§ Infant Mortality Rate

§ Second-Year Mortality Rate

§ Rate Of Low Birth-Weight Babies

§ Life Expectancy.

These rates are influenced by nutritional status and may thus be indices of nutritional status (2) (7).

· Data on morbidity like:

o Hospital Data

o Data from Community Health And Morbidity Surveys

particularly in relation to Protein Energy Malnutrition, Anaemia, Xerophthalmia and Other Vitamin Deficiencies, Endemic Goitre, Diarrhoea, Measles And Parasitic Infestations can be of value in providing additional information contributing to the nutritional status of the community especially in the children (2)

3. Ecological studies

Malnutrition is the end result of many interacting ecological factors. Therefore in any type of nutritional assessment, it is useful to collect ecological information of the given subject, population group or community in order to make the nutrition assessment complete.

A study of the ecological factors comprise the following :

o FOOD BALANCE SHEET :

This is an indirect method of assessing food consumption, in which supplies are related to census population to derive levels of food consumption in terms of per capita supply availability (2) (7).

However, the estimate refers to the country as a whole, and so conceals differences which may exist between regions, and among economic, age and sex groups. The great advantage of this method is that it is cheaper and probably simpler than any method of direct assessment. Used properly, this method does give an indication of the general pattern of food consumption in the country (2).

o SOCIOECONOMIC FACTORS :

Food consumption patterns are likely to vary among various socioeconomic groups. Family size, occupation; income, education, customs, cultural patterns in relation to feeding practices of children and mothers, all influence food consumption patterns (2).

o HEALTH AND EDUCATIONAL SERVICES :

Primary health care services, feeding and immunization programmes should also be taken into consideration (2).

o CONDITIONING INFLUENCES :

These include parasitic, bacterial and viral infections which precipitate malnutrition. It is necessary to make an "ecological diagnosis" of the various factors influencing nutrition in the community before it is possible to put into effect measures for the prevention and control of malnutrition (2).

Bibliography

1.

|

EDES TE. Clinical Methods, The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations. 3rd ed. Walker HK, Hall WD, Hurst JW, editors. Boston: Butterworth Publishers; 1990.

|

2.

|

Park K. Textbook of Preventive and Social Medicine. Twenty First ed.: Banarsidas Bhanot Publishers; 2011.

|

3.

|

Aykroyd WR. Conquest of deficiency diseases : achievements and prospects Geneva : World Health Organization : World Health Organization ; 1970.

|

4.

|

Nnakwe NE. Community nutrition: planning health promotion and disease prevention: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2009.

|

5.

|

Simko MD, Cowell C, Gil JA. Nutrition assessment:a comprehensive guide for planning intervention: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 1995.

|

6.

|

Mason JB, Habicht JP, Tabatabai H, Valverd V. Nutritional Surveillance. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1984.

|

7.

|

Srilakshmi B. Nutrition Science. 2nd ed. New Delhi: New Age International (P) Ltd.; 2006.

|

8.

|

SERIES TR. EXPERT COMMITTEE ON MEDICAL ASSESSMENT OF NUTRITIONAL STATUS. TECHNICAL REPORT SERIES. WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION.; 1963.

|

9.

|

E. SM. Modern nutrition in health and disease Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1998.

|

10.

|

Organization WH. Training Course on Child Growth Assessment, Measuring a Child’s Growth Geneva: WHO; 2008.

|

11.

|

Ghai OP. Ghai Essential Pediatrics: CBS Publishers & Distributors pvt Ltd; 2006.

|

12.

|

WHO. Training Course on Child Growth Assessment. In WHO. WHO Child Growth Standards. Geneva; 2008.

|

13.

|

WHO. WHO Child Growth Standards. In Training Course on Child Growth Assessment. Geneva: WHO; 2008.

|

14.

|

Ogden CL, Flegal KM. Changes in Terminology for Childhood. National Health Statistics Report. ; 2010.

|